This morning I walked through the woods with my chin on the ground. Cold, bright Spring morning, alone with a very handsome dog in the woods, feeling heavy. Body and spirit made of lead.

Does it matter why? Parenting, adhd, eldercare? The reign of cruelty in the US? Two weeks away from the woodworking studio?

When heaviness comes, after a period of fleeing, eventually I remember to stay. That shifts everything.

Fleeing can be days of agony—tension, leading to anxiety, leading to insomnia, leading to a giant human scribble.

I’ve learned to believe fiercely in self-compassion practice but I must admit, I do sometimes go there seeking escape, trained mindfulness mentor or not. It’s why these last days self-compassion hasn’t budged the iron padlock of my heart/mind.

When I’ve tried all the things and nothing heals the heaviness, eventually I have to get serious about staying. It’s what I did in the woods today. Ok pain, so you’re here. You’re not leaving, I get it. Let me know you completely, then. Tell me the worst of it.

I’m claustrophobic and I worry about getting stuck in elevators. But you know what I imagine? First I really freak out and have a proper fucking panic and then I sit down, calm down, start connecting with the other people in the elevator and make some friends. Lifelong friends? Maybe! The panic comes and goes in waves and then eventually we get out.

Well, either that or we suffocate. Starve, drink our pee, eat each other’s arms. Become nothing.

Do I have a say over which? I can take the stairs and often do, but I haven’t fully given up on elevators. Exposure therapy is highly effective.

Staying with discomfort, in a mindful way, is exposure therapy. Mindful is just awareness + compassion. (Don’t stay in the elevator without kindness or you’ll devour your only meat source, then starve anyway! What good was that!? You could have had a lifelong friend!)

My teacher, Tara Brach, tells a Buddhist story about the great Tibetan yogi Milarepa:

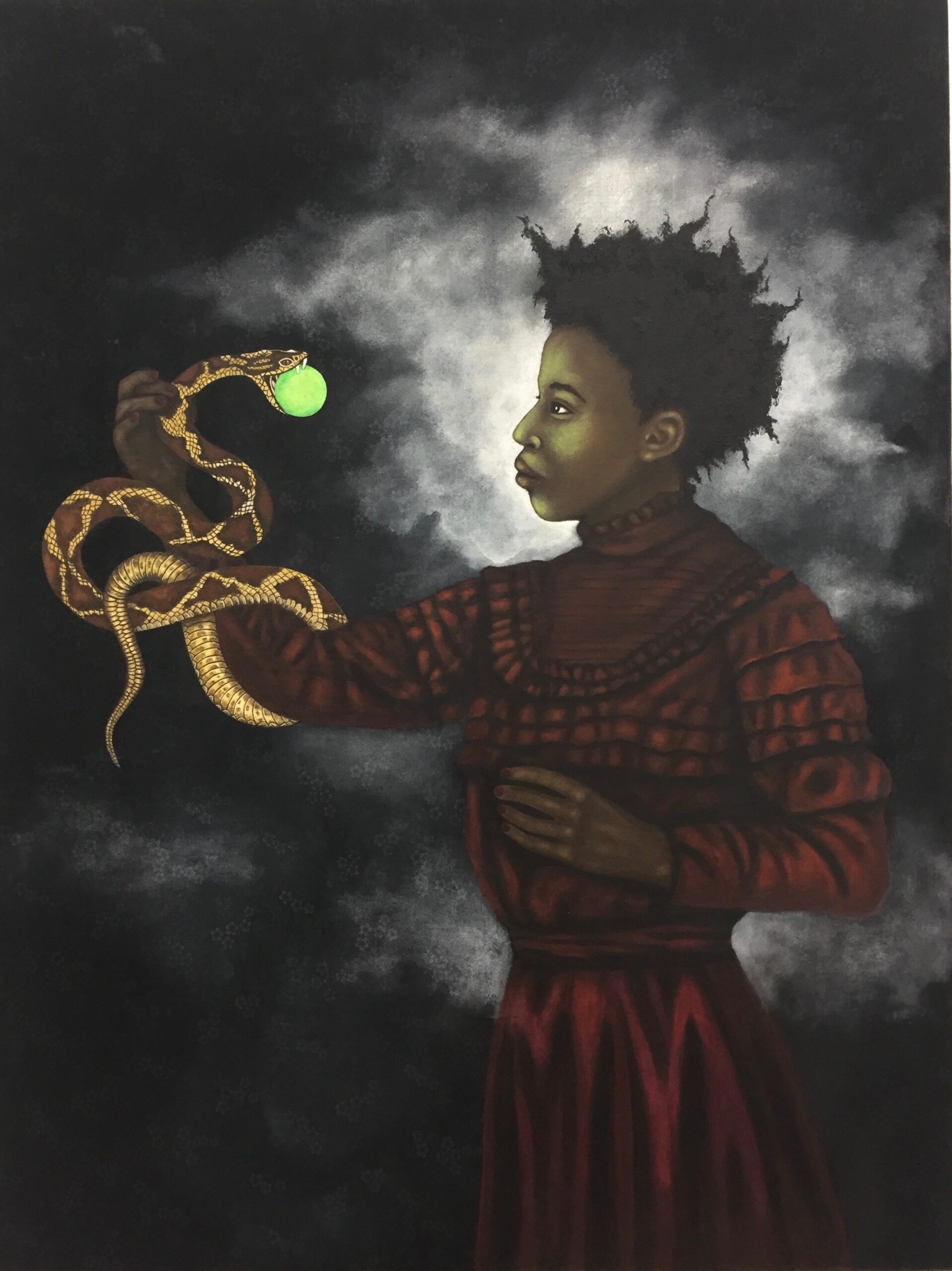

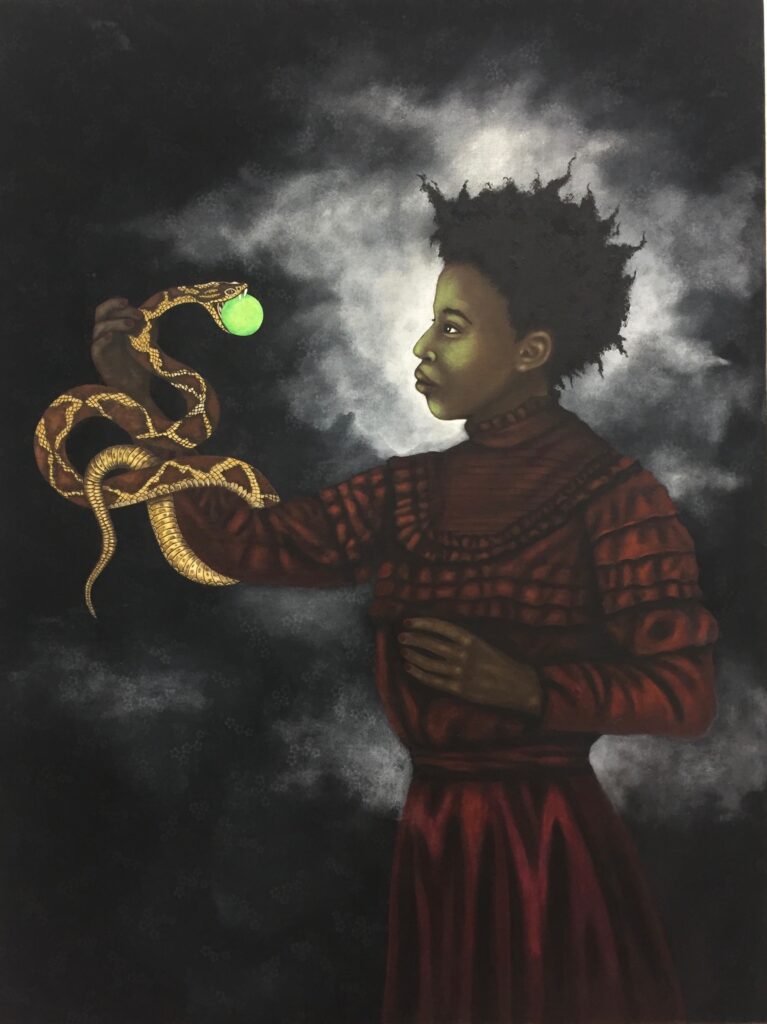

“Milarepa spent many years living in isolation in a mountain cave. As part of his spiritual practice, he began to see the contents of his mind as visible projections. His inner demons of lust, passion, and aversion would appear before him as gorgeous seductive women and terrifying wrathful monsters. In face of these temptations and horrors, rather than being overwhelmed, Milarepa would sing out, ‘It is wonderful you came today, you should come again tomorrow … from time to time we should converse.’ Through his years of intensive training, Milarepa learns that suffering only comes from being seduced by the demons or from trying to fight them. To discover freedom in their presence, he has to experience them directly and wakefully, as they are. In one story, Milarepa’s cave becomes filled with demons. Facing the most persistent, domineering demon in the crowd, Milarepa makes a brilliant move—he puts his head into the demon’s mouth. In that moment of full surrender, all the demons vanish. All that remains is the brilliant light of pure awareness. As Pema Chodron puts it: ‘When the resistance is gone, the demons are gone.‘”

Years of practice and teaching and still I resist. The monster is in the elevator. Turning toward it is hard. Letting it take my head in its mouth as if to end me, paradoxically, is a way to live.